A Prickly Problem

October 5, 2022 7:03 am

By Ellen Powell, DOF Conservation Education Coordinator

Did you know that one of Virginia’s State Forests was established specifically for research on a single species? That site is the Lesesne State Forest, located at the base of Three Ridges Mountain in Nelson County. The species is the iconic American chestnut (Castanea dentata).

American chestnut was once so abundant and ecologically important that it was considered a foundation species. But in the early to mid-1900s, the trees were decimated by an introduced fungal pathogen called Cryphonectria parasitica, or chestnut blight.

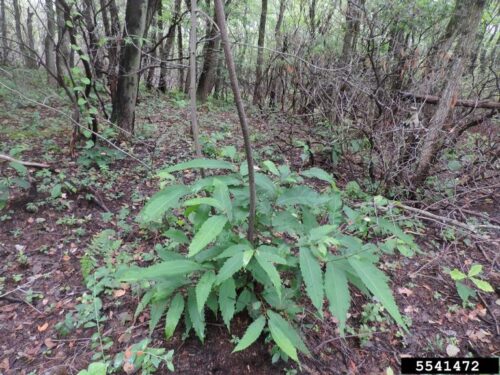

Although American chestnut is considered functionally extinct in the wild, trees can be found all over Virginia’s mountains. Century-old roots continue to sprout repeatedly. The resulting trees eventually succumb to the blight. But like a phoenix from the ashes, the roots send up hopeful shoots, again and again.

For many years, DOF has worked with other groups, such as universities and the American Chestnut Foundation (ACF), in seeking ways to restore American chestnut to eastern forests. Twenty-three seniors from Albemarle County’s Environmental Studies Academy (ESA) recently got a crash course in DOF’s research during a field tour of the Lesesne.

- Jerre Creighton addresses ESA students

- John Scrivani shows the canoe-shaped leaf of a pure American chestnut

The day was windy, and the group moved carefully through the orchard, trying to avoid being pelted by falling chestnuts, or worse, the prickly burs. DOF research manager Jerre Creighton and DOF research technician (and ACF Virginia chapter president) John Scrivani explained the heritage of most of Lesesne’s trees. Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima) is both the original source of the blight and the source of potential immunity. By cross-pollinating American with Chinese trees, then backcrossing the hybrids with pure American trees, researchers try to create mostly-American trees that can resist the blight. On the day of the students’ visit, DOF staff had just finished harvesting nuts for future planting.

- Heavy gloves are needed for picking chestnuts.

- View from the bucket truck

Breeding immunity into chestnuts has been a major strategy for years, but scientists recently discovered that a great many genes are involved in immunity. This may explain why backcrossing has been less successful than expected. In one of the chestnut orchards, the students observed blight cankers of varying sizes on almost every tree.

Occasionally, mature wild chestnut trees are found, often in remote locations. DNA analysis can determine if these trees are 100 percent American. If so, they probably carry some natural resistance to the blight. These trees may eventually help to re-establish chestnut on the landscape.

ESA students study environmental issues that are often complex and sometimes controversial. They must consider multiple perspectives and explore potential solutions. Chestnut recovery offers one such challenge. The best hope for reintroducing chestnuts may lie in transgenics – the introduction of genes from another plant.

The chestnut blight fungus produces oxalic acid, which kills tree cells. Some plants, including wheat, secrete an enzyme that destroys this acid. Scientists at the State University of New York (SUNY) introduced the relevant wheat gene into chestnut, and the resulting trees show remarkable blight resistance. SUNY needs approval from several federal agencies to begin planting nuts from these trees outside their tightly controlled experimental orchards. Some people are wary of genetic engineering and its potential effects on pollinators, wildlife, humans, and the rest of the ecosystem. Jerre Creighton asked the students to ponder this question: is restoring a foundation species worth the unknown risks that could come from altering its genetics? These are the types of questions the ESA students will grapple with as they move on to college coursework and eventual careers.

Before they left, the ESA students spread out through the orchard and spent twenty minutes journaling. Nature journaling combines scientific practice with writing and art – a good way to synthesize information after a day in the field, and perhaps, to come up with new ideas.

Lesesne State Forest is one piece in the complex puzzle of American chestnut’s restoration. It’s also a lovely spot to visit. If you go, walk the trail alongside the orchards, and you may be inspired by the tree that tries and tries again, refusing to give up in the face of adversity.

Chestnut resprouting from roots; photo by Richard Gardner, bugwood.org

Tags: Forest Health Impacts, Native Species

Category: Education, Forest Health, Research, State Forests